U.S. founding father Benjamin Franklin originally shared his famous “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure” advice to his home city of Philadelphia about fire safety. This maxim has since guided decision making in areas from natural disasters to public health.

It is time we apply this lesson to mitigating the impact of climate change, as the benefits of preventing carbon emissions versus undoing emitted carbon dioxide (CO₂) become enormous at the needed gigaton scale: trillions in investment today prevents quadrillions spent on disaster relief.

This means investing in the development and deployment of carbon avoidance technologies, which produce the goods and services the world’s population needs without emitting more CO₂.

Approaches to fighting climate change fall into three categories: adopting new technologies that don’t emit, capturing CO₂ at the emissions source, and pulling circulating CO₂ out of the atmosphere with direct air capture (DAC).

I liken this to the three ways of addressing a broken gushing faucet: you can fix the tap, put a bucket under the leak, or mop up the resulting water off the floor.

In a world of abundance, it is logical to fight climate change on all fronts. However, we are currently underspending by as much as $3.5 trillion per yearin our pursuit of net zero by 2050, according to McKinsey. We need to ruthlessly prioritize our resources to prevent the most catastrophic impacts of climate change and avoid reaching the point of no return.

This means at best picking two of out the three fixes: avoidance, point-source carbon capture and storage (CCS) and direct air capture. To have a swift, massive, and enduring impact we must invest in and catalyse technology that will allow us to avoid CO₂ emissions in the future while deploying point-source carbon capture to limit emissions immediately.

Investment in carbon avoidance solutions has proven successful in utilities, transportation, and heating — solar, wind, electric vehicles (EVs) and heat pumps have proliferated in large part because of government incentives and funding.

New carbon avoidance technologies in industrial manufacturing have emerged but cannot yet benefit from these programmes. While research and development of efficient DAC technologies is worthwhile as it will be needed in the future, the levels of funding should be based on the logical times of deployment, with industrial carbon avoidance technologies being deployed immediately and DAC deployed once the more efficient approaches are exhausted.

Back to my original analogy, mops are needed, but large-scale mop deployment at this time — while avoidable carbon is still pouring into the atmosphere — is not the highest and best use of our current precious resources.

CCS is an efficient near-term choice because the higher concentration of CO₂ in industrial flue gas — ranging from 13% to 30% — enables a much less expensive clean-up than DAC, with CO₂ at .04% of the atmosphere. This also buys us the time to scale the best option: carbon avoidance technologies, which are ultimately cheaper, more resource efficient, and prevent many decades of future emissions.

Carbon avoidance more cost-effective

Adding CCS infrastructure to an existing industrial process will always increase capital and operating expenses. For example, today’s ordinary portland cement (OPC) manufacturing releases nearly a tonne of CO₂ for every tonne of cement produced.

To decarbonize every OPC plant, you need an equally sized CCS plant tacked on. Carbon avoidance technologies bypass these clean-up expenses to deliver goods at cost-parity, once scaled.

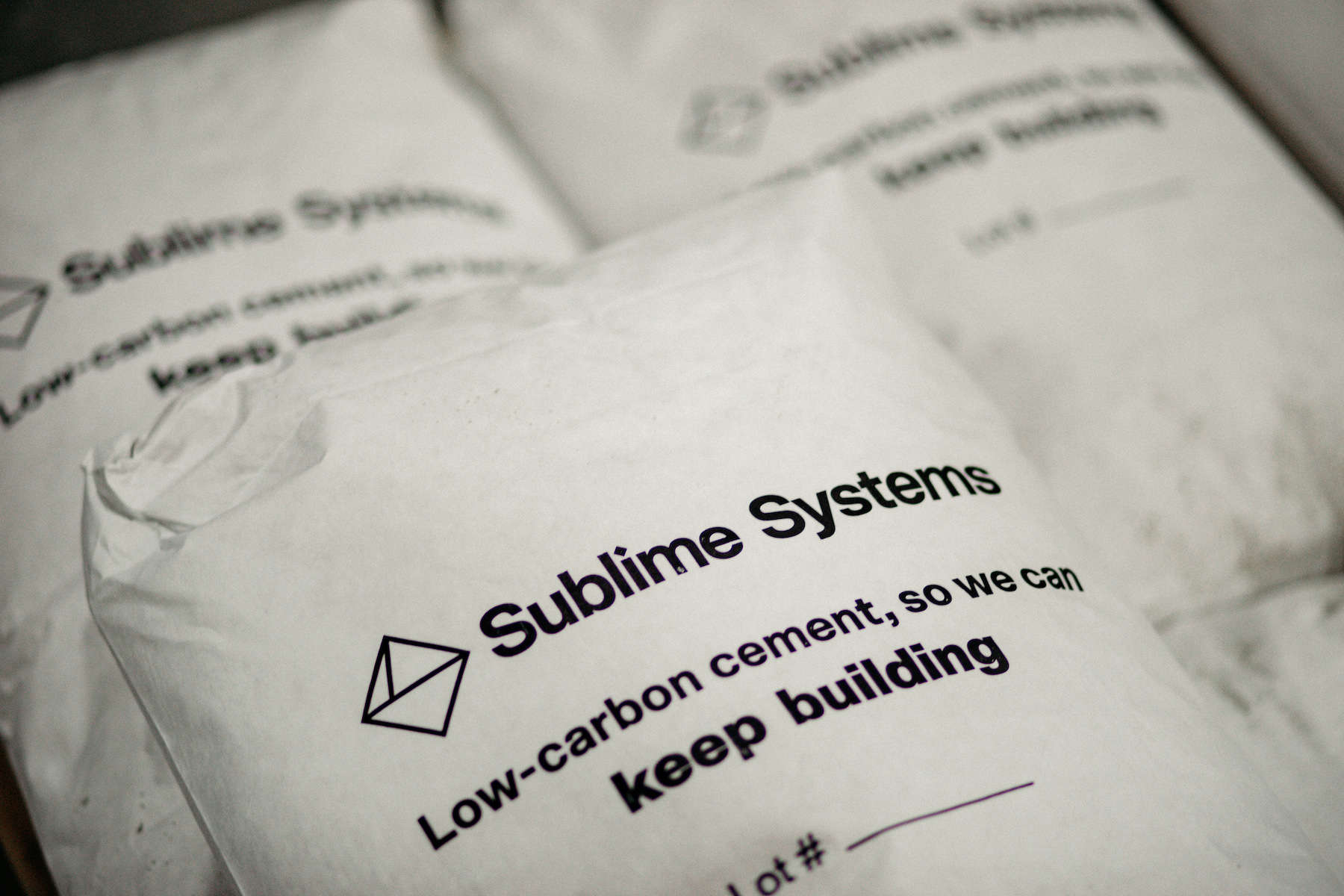

At Sublime Systems, we are taking this route with an electrified production process that uses electrolyzers and non-carbonate minerals to make cement instead of fossil-fuelled kilns and limestone.

Like many avoidance approaches, Sublime’s process yields a product with cost-parity at scale to today’s high-emitting options, as well as a cost-effective reduction of CO₂ emissions, as the below figure shows.

Carbon avoidance is resource efficient

People often view the fight against climate change as one of sacrifice, but many carbon avoidance technologies produce the same quality product — often with greater energy efficiency. Electric arc furnaces and direct-reduced iron for steelmaking, electric heat pumps for buildings, and new industrial wastewater filtration processes like Via Separations are great examples of this.

We must not only use our financial capital wisely to reduce emissions: we must be wise with the use of still-limited renewable electrons. We don’t (yet) have enough renewable energy to meet its many demands — in fact renewable energy deployment needs to triple if we are to meet net zero by 2050.

In the meantime, we must decide how to deploy precious renewable electrons by comparing the amount of CO₂ abated per kilowatt hour (kWh). Carbon avoidance technologies have the advantage here.

Sublime’s process for making cement is a particularly impactful use of renewable electrons because it not only eliminates fossil fuel emissions but also avoids the emissions from carbon-intensive limestone, thereby offering even greater decarbonization per kWh than many other carbon avoidance technologies — including EVs, heat pumps and hydrogen.

Clean technology of the future

Investment in a carbon avoidance asset also eliminates decades of future emissions, while accelerating the technologies that will become the enduring standards in our post-carbon future.

Both India and Africa are expected to roughly triple their cement production by 2050 from 2018 levels. Meanwhile cement and steel plants are designed and built to last 50 to 100 years; if we move quickly to deploy industrial carbon avoidance technologies in these industries, we can prevent a century of future emissions as developing countries enter a period of intense — but perhaps dirty — growth.

Despite their catalytic and enduring impact, carbon credits generated by industrial manufacturing avoidance technologies are valued less today than credits generated by carbon capture, creating perverse incentives to emit then clean up.

In voluntary markets, DAC credits command up to $600/tonne, while tech-enabled carbon avoidance credits are valued around $10/tonne — within the same range as hard-to-verify, nature-based solutions such as forestry.

The United States 45Q tax credit values CO₂ from point-source capture at $85/tonne and rewards a tonne of CO₂ removed by DAC at $180/tonne. Carbon avoided through efficiency or avoidance technologies receives $0. This redirects important financial and intellectual resources from the enduring fixes for the post-carbon world.

I urge policymakers and business leaders to consider the “leaky faucet” metaphor when creating policies and allocating resources. I urge them to invest in the development and deployment of carbon avoidance technologies wherever possible.

At the very least, I urge them to adopt technology-agnostic carbon credits and to value a tonne of CO₂ avoided the same, if not more, than a tonne of CO₂ captured and stored.

If we succeed at scaling carbon avoidance technology in time, we ultimately may not need to mop CO₂ from the air, nor will we have to invest in a more dire solution: climate adaptation and resilience. That is, in my leaky tap analogy, building an ark to navigate – or escape – the flooded room.

This article was originally published by the World Economic Forum.